Mass Spectrometry

- goodgreenlife

- Nov 27, 2025

- 5 min read

A short guide to Mass Spectrometry and Its Related Techniques

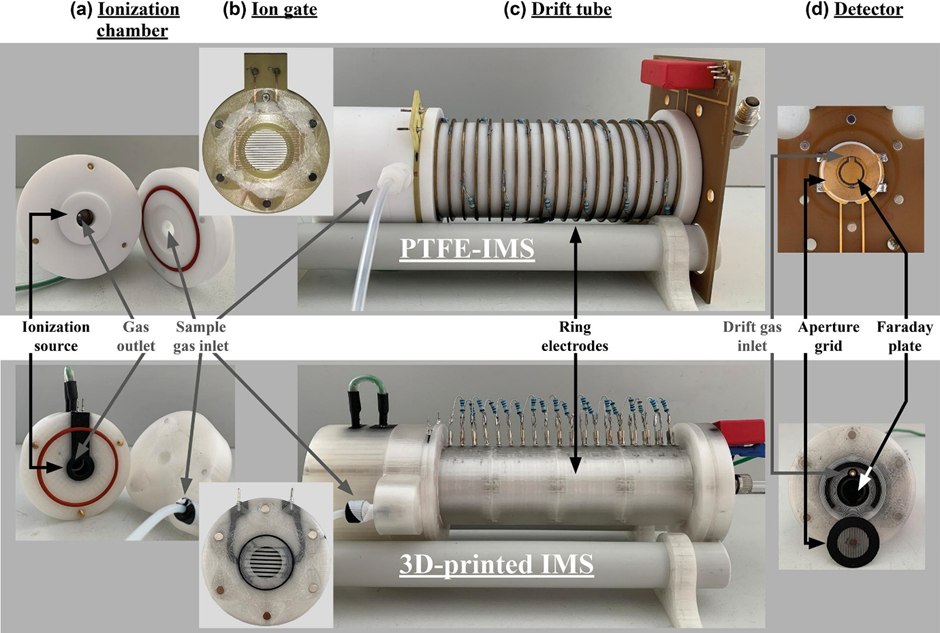

In this short guide I go over I outline the fundamentals of Mass Spectrometry (MS) and how it differs from other analytical approaches such as Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), Liquid Chromatography (LCMS), Paper Arrow Mass Spectrometry (PA-MS), Surface-Enhanced Ramen Spectroscopy (SERS), Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS).

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry is a highly effective qualitative and quantitative analytical technique used to identify and quantify a wide range of clinically relevant analytes. The data tends to be presented in units of the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of one or more molecules present in a sample. Where m refers to the molecular weight of the ion (in Daltons) and z is the number of charges present on the measured molecule. These measurements can be used to calculate the exact molecular weight of the sample components as well. It can be used to quantify known compounds, identify unknown compounds as well as determine structure and chemical properties of molecules.

It consists of 3 components: Ionization source, mass analyzer and an ion detection system

Ionization source

Molecules are converted to gas-phase ions so that they can be moved about and manipulated by external electric and magnetic fields. There are different ionization techniques but ultimately it creates positively or negatively charged ions depending on the experimental requirements. Neutral species go undetected as they are either absorbed by the apparatus or removed by a vacuum.

Mass Analyzer

Once the molecules are ionized, the ions are sorted and separated according to mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios. There are a number of mass analyzers currently available, each of which has trade-offs relating to speed of operation, resolution of separation and other operational requirements. They can either use electric, magnetic or both to separate ions, electric fields are most commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry.

Ion Detection System

The separated ions are then measured and sent to a data system where the m/z ratios are stored together along with their relative abundance. A mass spectrum is simply the m/z ratios of the ions present in a sample plotted against their intensities.

Before using the mass spectrometer, a sample must be prepared for ionization. This is typically done by converting it into either a liquid or gaseous phase using chromatography techniques. The 2 types of chromatography procedure that are used to prepare the sample are gas chromatography and liquid chromatography.

Gas Chromatography

GC–MS combines the separation power of Gas Chromatography (GC) with the molecular identification power of MS (Fig 2.). GC separates compounds based on boiling point and volatility, allowing the mass spectrum of each component to be recorded individually. In gas chromatography the components of a sample are dissolved in a solvent and vaporized in order to separate the analytes by distributing the sample between two phases: a stationary phase and a mobile phase. The stationary phase is either a solid absorbant, termed gas-solid chromatography (GSC), or a liquid on an inert support, termed gas-liquid chromatography (GLC). GLC is most commonly used, GSC has limited application and is rarely used due to sever peak tailing and the semi-permanent retention of polar compounds within the column.

Carrier Gas (1) The carrier gas plays an important role and varies in the GC use, it must be dry, free of oxygen and chemically inert so Helium tends to be used. It is safer than hydrogen, similar in efficiency, has a larger range of flow rates and is compatible with many detectors. Other gases like N2, Ar, H2 can be used depending on desired performance with H2 and He2 being commonly used on traditional detectors such as Flame Ionization (FID), thermal conductivity (TCD) and Electron capture (ECD). There are more detector types however we will focus on Mass Spectrometers as they are the most powerful of all the detectors.

Sample Injection (2 & 3)

A calibrated microsyringe is used to deliver a sample volume in the range of a few microlitres through a rubber septum and into the vaporization chamber. The chamber is typically heated to 50 °C above the lowest boiling point of the sample and subsequently mixed with the carrier gas to transport the sample into the column.

Column Oven (4)

The column oven temperature must be accurately controlled to ±0.1 °C. The oven temperature can be operated in two ways, either isothermal programming or temperature programming. In isothermal programming, the temperature of the column is held constant throughout the entire sample, optimally are the middle point of the boiling range of the sample. This works well if the boiling point range of the sample is narrow. If it wide, and you chose a low temperature the low boiling fractions are well resolved but the high boiling fractions are slow to elute with extensive band broadening. If the temperature is towards the higher end, the high boiling point components elute as sharp peaks, but the lower boiling point components elute so quickly there is no separation.

Temperature programming allows you to start at a low temperature to resolve the low boiling components and increase the temperature during the separation to resolve the less volatile high boiling point components.

Open Tubular Columns and Packed Columns (4)

The most common mass analyzer are a quadrupole mass analyzer with EI ionisation (Electrospray ionisation formerly known as electron impact ionisation)

Detector (5)

The mass spectrometer acts as the detector, providing far more information than traditional GC detectors such as FID or TCD.

Computer (6)

The computer software converts the electrical signals from the detector into a chromatogram, which plots signal intensity against retention time. Each peak represents a compound eluting from the column, with peak height or area corresponding to its relative abundance. At every point in the chromatogram, the system also stores a full mass spectrum, which displays the m/z ratios and intensities of the detected ions. This combination of retention time and spectral information enables robust compound identification and quantification. Modern software can deconvolute overlapping peaks, search spectral libraries, integrate peak areas, and produce calibration curves. Together, the chromatogram and spectral data form a detailed digital record of the chemical composition of the sample, allowing analysts to interpret even highly complex mixtures.

For additional detail please see the ChromSoc2025 post which goes into great detail on GC-MS.

PA-MS, SERS and IM-MS will talked about in a future post.

Extra resources on MS and GC-MS: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589702/, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjXBwbGG0e8

Comments