World records in metabolomics and Extreme environment MS

- goodgreenlife

- Dec 25, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Jan 6

After looking at metabolomics from first principles and attempting to differentiate the current advantages and limitations of technologies for its profiling, I would like to investigate a strong front runner technology for a potential home diagnostic device, Mass Spectrometry (MS). GC-MS and LC-MS are the traditional gold standard for metabolomics research but when looking at the frontiers of research and innovation there are other powerful variations of MS technology.

World records in metabolomics as well as how it has been applied in extreme environments, offer a view on its capabilities and limitations. The frontier of science always has technological innovations that have positive effects for the overall advancement of a field. Here in I will describe current achievements in metabolomics, such as profiling incredibly complex mixtures, very large molecules as well as take examples from the Harsh Environment Mass Spectrometry group (link).

Highest Mass Resolution

FTICR-MS has been mentioned a few times in both this article and others, this is due to it simply being the best technique for analysing complex molecules mixed together in a fluid. The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (link) due to their focus on extremely strong magnets are the forefront of a lot of this research.

FT-ICR can enable you to look at very complex mixtures for example crude oil, but in order to differentiate two distinct molecules it’s a real challenge. Scientists at MagLab were able to differentiate between two distinct molecules that were only about 0.000452 Dalton apart in atomic mass. That’s about as much as an electron weighs.

Just to re-iterate how FT-ICR works. After ionisation, the molecules are guided into a Penning trap which is located in the centre of a super conducting magnet. Due to the vacuum system, ions are able to spin circles more than 100,000 times without colliding into another particle. Though the orbit radius is about the same for all of the divergent ions, the speed at which they travel is not and is determined by each ion’s mass. Known as their cyclotron frequency, lighter ions travel fast and have higher cyclotron frequencies.

These frequencies increase as the power of the cyclotron’s magnet increases. So, when the frequencies increase so does the difference between any two ICR frequencies which means it’s easier to tell the different types of ions apart. Thus improving the frequency.

Highest Magnetic Field for FT-ICR Mass Spectrometry (link)

In 2014 the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory and the Bruker Corporation installed the world’s first 21 tesla magnet for FT-ICR. The tool represents the world’s highest field, persistent, superconducting magnet suitable for FT-ICR mass spectrometry.

The MagLab's ICR Program is a world leader in instrument and technique development, as well as in pursuing novel applications of FT-ICR mass spectrometry, and the 21 T will allow scientists significantly greater insight into materials. Said Professor Marshall: "Three primary science drivers for this instrument are: (a) faster throughput without loss of mass resolution for top-down proteomics; (b) extension of the size and complexity of protein complexes whose contact surfaces are mapped by solution-phase hydrogen/deuterium exchange, and (c) improved mass resolution and dynamic range for characterizing compositionally complex organic mixtures (petroleum, dissolved organic matter, metabolome). The higher magnetic field should result in dramatic improvement (by factors of 40-100%) in FT-ICR MS figures of merit, including mass resolution and resolving power, mass accuracy, dynamic range, and data acquisition speed."

Scientists in Zurich in 2005 have set a world record in mass spectrometry by observing the largest ever mass-to-charge ratio of over 1 Mio Dalton (MDa). Researchers in the team at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology had to overcome several obstacles including the intact vaporisation and ionisation of the sample as well as the detection of the very large ions.

They used modern soft ionisation techniques on immunoglobulin M (1 MDa) and a group of blood coagulation proteins known as the von willibrand factor (1.5 and 2 MDa). In order to detect ions of the magnitude, they used a superconducting tunnel junction detector developed by Swiss firm Comet AG.

For this record they used an Orbitrap analyser using a frequency chasing method. They found that large ions can easily survive multisecond-long transients. Notwithstanding the fact that they experience a multitude of collisions with background gas molecules during that time. The energy deposited by these collisions does not cause fragmentation as is the case for small denatured ions, but does lead to gradual solvent loss accompanied in rare instances by charge stripping events. These events are the underlying processes of temporally unstable frequencies, resulting in Fourier transform artefacts, impairing the performance of Orbitrap-based CDMS (Charge-detection mass spectrometry).

Using this modified frequency-chasing method it allowed them to extend the transient recording times even further while minimizing Fourier transform artefacts, revealing mechanisms of signal decay that are distinct from those observed in a FT-ICR. Such long transient recording additionally enabled the first ever experimental observation of the radial ion motion in an Orbitrap analyser. Moreover, based on our observations of the behaviour of single ions within the mass analyser, we introduce multiple improved data acquisition strategies for Orbitrap-based CDMS. In combination, these improvements lead to a substantial improvement in effective ion sampling, resulting in better statistics and, by harnessing longer transient data, an almost twofold increase in mass resolution.

Largest Number of unique Compounds in a Single Sample (link)

In 2022 Katharina Kaiser from IBM Zurich used high-resolution atomic force microscopy to identify individual molecules from Murchison meteorite samples. This a meteorite that fell in Australia in 1969 near Murchison Victoria. The oldest material found on Earth to date are the silicon carbide particles from the meteorite which have been determined to be 7 billion years old, 2.5 billion years older than the 4.54 billion year age of the Earth and the Solar System. Previously FTICR-MS (Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry) via ESI (electrospray ionisation) revealed 14,000 molecular formulas.

To resolve very rare species in the sample and get down to single molecule sensitivity, atomic force microscopy was used. Obtaining atomic resolution and identifying individual compounds by AFM effectively complements the information obtained using NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance), GC-MS (Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) and FTICR-MS, from here they were able to detect over 10,000 unique compounds at very low concentrations from a single extract.

Most Molecular Formulae Assigned in a Single Run (link)

Scientists at the University of Warwick have been able to assign a record-breaking 244,779 molecular compositions within a single sample of petroleum. The developed a new method called operation at constant ultrahigh resolution (OCULAR) that combines experimental and data processing techniques that allowed them to characterise the most complex sample that they have ever worked on. This approach OCULAR (Operation at Constant Ultrahigh Resolution) makes it possible to analyse samples that were previously too complex even for high field FT-ICR MS instrumentation. Previous FT-ICR MS studies have typically spanned a broad mass range with decreasing resolving power (inversely proportional to m/z) or have used a single very narrow m/z range to produce data of enhanced resolving power. Meaning the resolving power decreases significantly with increasing m/z. Both methods are of limited effectiveness for complex mixtures spanning a broad mass range.

This OCULAR approach, they recorded a record number of unique molecular formula without the aid of chromatography or dissociation MS/MS experiments. This method can be used with FT-ICR MS instruments to enhance their performance.

As an aside there have been other incredible records. For example, in 2014,(link) absorption mode data was used to establish world records using an underwater asphalt volcano sample: a resolving power of 1 400 000 FWHM was demonstrated at m/z 515, with 85 920 molecular compositions assigned. In early 2018, two 21 T FT-ICR mass spectrometers in different laboratories were applied to the analysis of complex mixtures; one achieved a resolution of approximately 1 000 000 FWHM at m/z 2700 using absorption mode (6 s time-domain transient)(link) and the other a resolving power of 2 700 000 FWHM at m/z 400 using absorption mode (transient length of 6.3 s), with an accompanying assignment of 49 000 molecular compositions (link).

An article is needed to discuss the OCULAR workflow due to its impact on FWHM.

Quadrupole filters are typically employed in mass spectrometry to isolate particular ions for analysis. However, a limitation of them is that you throw away up to 99% of the useful ion signal and this caps the speed at which fragmentation data can be generated. The solution is high-resolution ion mobility (HRIM) which offers a means to quickly and efficiently isolate ions prior to fragmentation and detection by a high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) while also resolving challenging isomeric and isobaric compounds that lead to chimeric MS/MS spectra.

Isomeric compounds – molecules with the same molecular formula but different arrangement of atoms, leading to distinct structures and physical properties like boiling boings.

Stereoisomer – same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms but differ in spatial arrangement of atoms

Isobaric compounds – molecules with different chemical formulas but the same nominal mass for example C2H4 and CO.

Chimeric MS/MS spectra – when you sequence two or more distinct molecular ions which are similar in mass and co-elute within a small time window.

HRIM isolates ions in time as result of a high-speed separation rather than acting as a filter that discards ion signal like quadrupole mass analyser. As HRIM eliminates the need to hop or sweep electronics control parameters, fragmentation spectral generation can occur at a much faster rate, upwards of 500 Hz. The concept is known as structures for lossless ion manipulation (SLIM).

Conventional MS/MS workflows force a trade-off, data-dependent acquisition (DDA) yields clean, specific spectra but scans too slowly to catch all peptides, whereas data-independent acquisition (DIA) is fast and unbiased yet produces multiplexed (“chimeric”) spectra that complicate analysis. A key limitation is the quadrupole mass filter isolating one precursor at a time, it passes one ion species while discarding others, limiting sensitivity and speed. MOBILion’s approach eliminates this bottleneck using Structures for Lossless Ion Manipulation (SLIM) for ion mobility separation and a novel Parallel Accumulation with Mobility-Aligned Fragmentation (PAMAF) mode. SLIM is a long-path, high-resolution ion mobility device (ions traverse ~13 m in a serpentine RF-guided path) that achieves resolving power >250, enough to distinguish ~0.2% differences in collision cross section. This high-resolution ion mobility (HRIM) stage separates co-eluting ions by drift time. In PAMAF mode, SLIM effectively replaces the quadrupole: it spreads ions out temporally by mobility so that up to 100% of ions can be transmitted, fragmented, and detected in parallel without mutual interference. This enables near-total ion utilization, dramatically boosting MS/MS efficiency.

Using SLIM+PAMAF, MOBILion achieved >1,337 Hz MS2 acquisition (535 MS/MS scans in 0.4 s), likely the fastest tandem MS collection reported. Fragmentation duty cycle and sensitivity are vastly improved: replacing slow sequential isolation with mobility separation yields ~10× higher MS/MS signal-to-noise and ~5× faster scan speeds than conventional systems. Practically, this marries the strengths of DDA and DIA – comprehensive coverage at high speed and high spectral clarity. Mobility-separated fragmentation produces far fewer chimeric spectra, so spectra remain clean and identifiable even as the method captures nearly all precursors across an LC peak. Achieving ~2.5 ms per MS/MS scan is a breakthrough for real-time, high-throughput mass spectrometry, overcoming the long-standing trade off between depth and speed. In proteomics and other omics workflows, such extreme MS2 speed and efficiency promise deeper proteome coverage and more precise quantification in each run. Researchers can contemplate analysing complex samples (even single cells or very short LC separations) without losing information to instrument speed limits.

Underwater Mass Spectrometers (Girguis group, link)

At the Girguis Lab, they study how animals such as fish, clams, mussels, snails and worms form a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. A lot of their work is at deep sea vents and seeps where many animals harbour intracellular “chemosynthetic” bacterial symbionts that harness energy from chemicals in vent fluid. They use this energy to convert inorganic carbon to sugars which they share with their hosts and are the primary source of nutrition for the animals. This partnership works so well that, in many cases, chemosynthetic vent communities can be more productive than rainforests and kelp beds.

In the Ocean, many chemical species of interest are present as dissolved gases and volatile compounds. Conventional ex situ water sampling techniques require the manual collection, storage and transport of samples to the laboratory. Sampling artifacts are prevalent due to the physical and chemical changes such as degassing and biological degradation that may occur during transport. For example, pressure and temperature have a pronounced effect on methane solubility and so upon retrieval of methane-saturated water samples from the deep ocean, methane rapidly outgasses to the atmosphere.

Many in situ techniques such as oxygen optodes and tin oxide sensors have been developed to overcome the limitation associated with off-site sampling. However, though they have helped advanced our understanding of the ocean and low detection limits (nM levels) they have their own draw backs. They are limited to detecting one or a few gas species at a time, meaning that multiple sensors are required to survey a broad spectrum of gases at once. Single parameter measurements such as tin oxide sensors surfer from a lack of sensitivity. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as toluene, benzene and dimethylsulfide (DMS) may be detected via IR spectroscopy, but this method is restricted to the surface ocean and coastal waters.

Underwater mass spectroscopy (UMS) allows you to analyse a range of species using a single system. They can also detect many dissolved gases at the ppm level and VOCs at the ppb level within a matter of seconds or minutes. It also allows for continuous 3D measurements of a variety of gases and other volatile species in real time, as well as the potential for high-resolution mapping. Membrane Inlet Mass Spectrometry (MIMS) was pioneered by Hoch and Kok (link). The primary consideration for MS underwater is how dissolved analytes are introduced into the high vacuum of the mass spectrometer. In MIMS, a volatile sample passes directly from the environment into the mass spectrometer through a selectively permeable membrane. MIMS requires minimal-to-no sample preparation and employs simple and robust inlets. It enables simultaneous measurement of multiple chemical species with unique mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios from a single sample. Analyte concentrations can be measured from the parts-per-hundred to parts-per-trillion levels on timescales of a few seconds to minutes.

In situ mass spectrometry analysis is only feasible if the requisite instrumentation is field-portable, and so the mass analyser must be miniaturized. Magnetic sector, time-of-flight, linear quadrupole, ion trap, and cycloidal mass analysers are the types of mass analysers that have been miniaturized successfully. Most UMS systems employ linear quadrupole mass filters, which are robust, compact, and relatively inexpensive. The power requirements for quadrupole mass filters contribute significantly to the overall system's power consumption, as they must operate using rather high direct current (DC) and radio frequency (RF) voltages applied to the four rods of the analyser.

Ion traps have also been used in UMS systems and have a wider mass range than linear quadrupoles or small cycloidal analysers (650 amu vs. a few hundred amu). However, the membrane inlet typically limits the range of m/z of compounds introduced into the mass spectrometer to <300 amu, so the full range of the ion trap cannot be utilized. Ion traps are highly sensitive, with detection limits up to 20 times better than some quadrupole mass filters, which is especially useful in environmental and trace monitoring. Ion traps can operate at even higher pressures than linear quadrupoles, and they can perform multiple stages of mass spectrometry with no modifications. Conventional size ion traps require high RF fields, however, and have much higher power requirements than linear quadrupoles, adversely affecting deployment length

The need for MS in space exploration has greatly increased the ability of miniature mass spectrometry systems due to the intrinsic needs of it being compact, lightweight, low power consumption, robust operation and a high tolerance to the harsh environment as well as be automated.

In an interview with Xiang Li and Ryan Danell two research scientists they discuss the challenges and abilities of MS systems. The purpose of MS in space is to identify traces of biosignatures. They need to develop sophisticated analytical techniques and refine their understanding of nuances that distinguish extraterrestrial biomarkers from other sources.

The Dragonfly mission to Titan uses laser desorption, that targets higher mass, non-volatile species. But for other missions like the Europan Molecular Indicators of Life Investigation (EMILI) mission, the subcritical water extraction capillary electrophoresis (CE) techniques has a high sensitivity to detect amino acids, which is a crucial group of compounds directly related to life detection.

Danell - “There are a lot of techniques available, but if you want the most powerful answer, mass spec is the way forward. It is very complicated, which makes it resource intensive (both cost as well as mass and power), as well as requiring highly trained individuals to work on the hardware. However, the generality of mass spec allows us to handle unknown samples, providing results from a single analysis without necessitating additional techniques and instrumentation. The detailed information provided by mass spec can be very informative, helping us advance our knowledge as we explore further into the universe.”

Portable GC-MS to Military Users for identification of Toxic Chemical Agents (link)

Recently, these systems were deployed to conventional military forces for use in theatre to detect and identify toxic chemicals including chemical warfare agents (CWAs). The challenges of deploying such complex analytical instruments to these military users are unique. Among other things, these organizations have considerable and variable mission strains, complex and difficult logistics and coordination needs, and variability in user backgrounds. This section outlines the value portable GC-MS systems offer to these war fighters in theatre, discusses some important aspects of the design of portable systems that makes their deployment to this type of end user possible, and proposes methods that can be used to overcome challenges to successful deployment of portable GC-MS to non-scientists working within hostile environments.

There are many methods used to screen and detect CWAs and TICs in the field. These methods range from simple colour tests capable of detecting different functional groups of the CWA or TIC molecule, to advanced methods such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) that can identify and even quantify the specific chemical composition of the CWA or TIC substance (link).

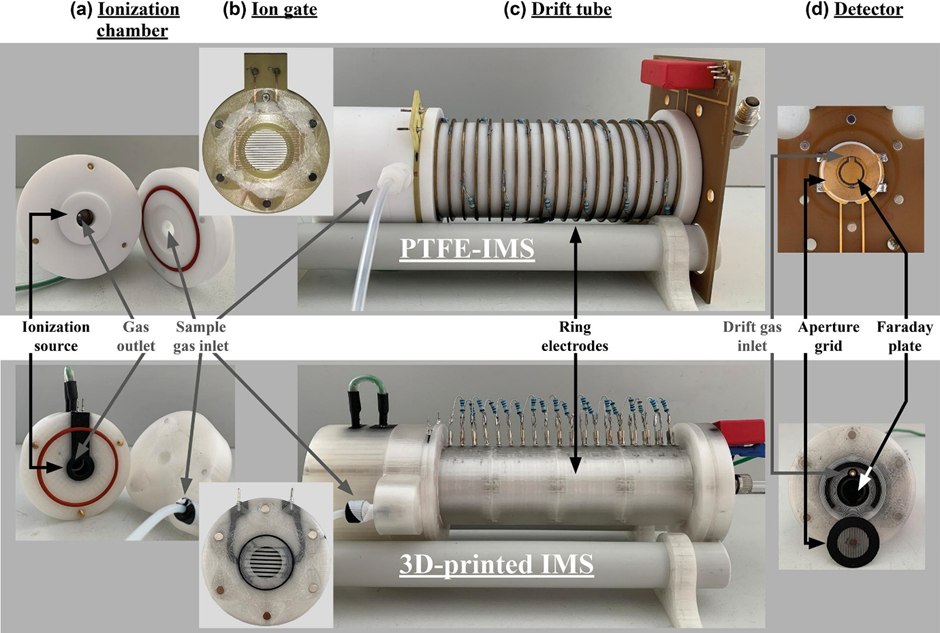

Portable GC-MS is valuable as a confirmatory method and likely offers the best potential for meeting the current and evolving analytical challenges of the military associated with CWA and TIC detection and identification in the field. First, the vapor pressure of many modern CWAs (link) is low and, therefore, detection limits for viable field detection and identification technologies need to be low (like they are for portable GC-MS). In addition, GC-MS systems integrate separation, identification, and quantitation capabilities, which is especially important for field applications where mixture samples are commonly encountered. Optical techniques including infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopies are valuable as bulk identifiers, but these methods are challenged by mixtures, especially when the component of interest is at low concentration. Other methods such as ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) can detect and presumptively identify trace residues of chemicals (in some instances down to a few nanograms or less), but not when these trace residues are in complex sample matrices. Portable GC-MS systems, on the other hand, can reliably and rapidly detect and identify these substances at low concentrations, even when the substance is masked in a complex matrix.

Conclusions

These are some incredible uses of mass spectrometers and signal both its need and its impact. Understanding more about the technology is important to apply it to omics, however the largest bottle neck in my goal may not be creating the prototype device of which you could argue already exists, but mass production. If health is to be democratised each unit has to be made on scale with a low cost per unit.

Comments